Global water point failure rates

Seen at the market in Serrekunda, The Gambia

In Between Politics and Humanitarian Agendas: UNRWA and Palestinian Statehood

Abstract

The United Nations Work and Relief Agency (UNRWA) is the oldest, most-established and perhaps the most successful international humanitarian operation in the world. It was set up as a temporary agency in 1949 to assist displaced Palestinians after the Arab-Israeli hostilities of 1948. Its original mandate was to carry out relief and work programs in cooperation with local governments. Over the years, the UN General Assembly repeatedly renewed UNRWA’s mandate while awaiting resolution of the question of the Palestine refugees. As the situation continued to remain unresolved, UNRWA’s services were extended to include relief, human development and protection of Palestine refugees. Although the agency’s mandate was intended to be temporary, its existence has nonetheless been perpetuated because of the intractability of the Palestine problem. Today, UNRWA’s services reach out to over five million Palestinian refugees, living primarily in the Gaza Strip, West Bank, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon.

This paper is concerned with the politics of humanitarianism, analyzing how geo-political relations influence the situation at the macro level and how that relates to the principles by which UNRWA is meant be guided. More specifically, I will analyze UNRWA’s policies and practices through both the humanitarian and political lenses, and the resulting influence on the lives of Palestinian refugees. I will study the trends within the organization, how the mission of the organization is guided by a new brand of humanitarian imperative, and comment on the future of the organization itself. My primary mode of research is the existing body of research referenced throughout this paper as well as an interview conducted with Mr. Lex Takkenberg, current Chief of Ethics Office and previous Deputy Director General at UNRWA.[1]My aim is to investigate the policies and schemas of intervention, their relation to the political agenda, effect on the socioeconomic status of the refugee households and implications on the Palestinian aspirations of statehood.

Introduction

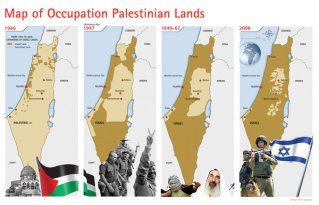

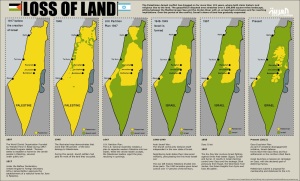

In the aftermath of 1948 Palestine War (al-Nakba), more than 700,000 Palestinian civilians were displaced from their homeland to become refugees either in cities and towns within what remained of Palestine or in countries outside Palestine[2]. Immediately after the 1948 war,emergency aid was channeled to Palestinians via international agencies and international non-governmental organizations. On 8 December 1949, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) was established by the UN under General Assembly Resolution 302 (IV) to provide assistance, protection and advocacy for Palestinian refugees. UNRWA defined a Palestinian refugee as, “person whose normal residence was Palestine for a minimum of two years before the 1948 Arab-Israeli war and who lost both home and livelihood as a result of the conflict and took refuge in one of the areas which today comprise Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and the West Bank and Gaza Strip.” This definition however has evolved over the years, as will be discussed later.

Currently, the total number of refugees who benefit from UNRWA’s services is over five million. UNRWA has been the main provider of basic humanitarian relief and human development services to the Palestinian refugees for more than 60 years. Over the years, the agency has provided services traditionally associated with government ministries in the fields of education, health, and social services, establishing itself almost as a quasi-state institution.[3] In spite of the Palestinian population being one of the highest per capita receivers of aid on a regular basis, the socioeconomic indicators for Palestinian households have not shown much improvement. Among some refugee groups, poverty is rampant, while the livelihoods of others have been taken hostage by the onslaught of war in Arab states. Moreover, the Palestinians remain a state-less population and 65 years latter are arguably no closer to a viable, sustainable solution.

These factors bring into question not only the impact of UNRWA’s work, but its approach to humanitarianism and even its reason for existence. On one hand, the severely under-funded organization has been questioned for the shortcomings of its rigor in providing humanitarian assistance, while on the other, its programs have been regarded as contradictory to the right of return of Palestinians. Only through an analysis of the evolution of UNRWA, its position in the geopolitical arena and scrutiny of its theory and methodology of change, can one attempt to answer these questions.

The Evolution of UNRWA

UNRWA was created by the UN General Assembly as a temporary humanitarian agency in response to the urgent problem of the Palestinian refugees. It is widely believed that UNRWA may have been created because of a misperception that the United Nations was responsible for the flight of the refugees from Palestine.[4] Hence, the General Assembly accepted the Palestinians refugees under its wards, until the umbrella of its protective agencies was no longer needed.Because UNRWA was created as an autonomous UN agency, directly accountable to the General Assembly and not incorporated as an international treaty, its accountability system has been flawed from the very beginning. Unlike UNICEF or UNHCR, the two welfare agencies which focus on formulating and coordinating programs, UNRWA executes its programs and has been the second largest employer in its field of operation.[5]The agency’s structure allows it broad freedom of action, making it capable of engaging in commercial transactions and establishing legally defined relations with governments, other international organizations, and employees.

In 1949, UNRWA served between 330,000 and 500,000 refugees. Today, this number has grown to over five million[6]. While initially UNRWA had a legal reason for existence, after the numerous efforts to settle the Israeli-Arab conflict, the UN replaced its initial legalistic approach with a humanitarian one. The 1967 conflict and the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip since then created new realities – there was an unexpected increase in the number of refugees and human rights became the new focus of attention.[7] UNRWA’s public works plan (to create permanent employment and build essential infrastructures in the camps) failed shortly due to resistance from both refugees and host country governments. Following this, there was a shift in focus to education, with health care and relief as second and third priorities. The intifada of 1987-1993 provided the next occasion for UNRWA to be called upon to implement “passive” protection activities in relation to the Palestine refugees. The UN Secretary General submitted a report to the Security Council in which was mentioned four principal means by which the protection of the Palestinian people in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT), including the refugees, could be secured: physical protection, legal protection, protection by means of general assistance and protection by publicity. UNRWA’s role was seemed primarily to provide general assistance while creating awareness of the situation. The Madrid and Oslo peace frameworks provided new hope for a meaningful solution, and redefined the role that UNRWA could play in it. The UN General Assembly noted that UNRWA should work within the framework of strengthened cooperation with host countries and the Palestinian Authority to make a pivotal contribution towards economic and social stability of the occupied territories. This endorsed UNRWA’s Peace Implementation Program designed to improve infrastructure and services for the refugees and in the camps in the OPT.

UNRWA remains unique in the UN system as an operational body whose primary relationship is with the General Assembly. It was intended as a temporary organization that would provide emergency relief to the Palestine refugees alongside other UN mechanisms that were designed to address the political issues in their entirety. The failure of the UN mechanisms designed to handle political issues of the Palestine problem has forced UNRWA to metamorphose into an all-purpose vehicle. The evolving contours of its mandate have reflected this. However, at its core, UNRWA’s mandate continues to be the provision of essential humanitarian services and the empowerment of the refugees through development of their human capital until there is a just solution to the refugee problem[8].

The Humanitarian Imperative and New Humanitarianism

Humanitarian action is defined as “International attempts to help victims through the provision of relief and the protection of their human rights”.[9] There is however an ethical framework that directs humanitarian work through the humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence as defined bellow.[10]

| Humanity | Human suffering must be addressed wherever it is found. The purpose of humanitarian action is to protect life and health and ensure respect for human beings. |

| Neutrality | Humanitarian actors must not take sides in hostilities or engage in controversies of a political, racial, religious or ideological nature. |

| Impartiality | Humanitarian action must be carried out on the basis of need alone, giving priority to the most urgent cases of distress and making no distinctions on the basis of nationality, race, gender, religious belief, class or political opinions. |

| Independence | Humanitarian action must be autonomous from the political, economic, military or other objectives that any actor may hold with regard to areas where humanitarian action is being implemented. |

Table 1: UNOCHA Humanitarian Principles

Humanitarian response has always been molded by politics, although this relationship is constantly evolving and depends on the geopolitical context. As a UN mandated humanitarian organization, UNRWA is bound by these UNOCHA humanitarian principles. While in theory, the agency strives towards these principles, geopolitics, funding, conflict and internal disagreements have had major implications on the practice of these principles. Many scholars have argued that “humanitarian intervention is increasingly becoming an integral part of western governments’ strategy to transform conflict, decrease violence and set the stage for liberal development”.[11] This changing role of humanitarian aid is often termed ‘New Humanitarianism’, and is seen as “an overt politicization of aid’’.[12] UNRWA’s directive to uphold the humanitarian principles can be in direct conflict to the foreign policy interests of governments, many of which are its primary donors. This is particularly true in areas of conflict such as Gaza and more recently in Syria. Palestinian refugees from Syria have been severely affected by the ongoing armed conflict, with virtually all of their residential areas experiencing armed engagements or the use of heavy weapons. UNRWA’s humanitarian initiatives for the 540,000 Palestine refugees in Syria has been at the mercy of the conflicting rebels and pro-Assad forces. Thousands of refugees have been stranded in camps that have been utilized as militant strongholds. This has led the Syrian government forces to lay siege on camps such as Yarmouk on the outskirts of Damascus, obstructing the delivery of aid by UNRWA for months at a time. Once again, the humanitarian imperative has come secondary to political interests.

Moreover, the international donor assistance community has continued to use disciplinary conditionality aimed at producing desired political and social change. This new-humanitarianism becomes vulnerable when it is financially dependent on donor countries with political interests. UNRWA must consider alternative sources and vehicles of funding in order to ensure that the humanitarian principles of independency is upheld.

One of the main debates about humanitarianism is whether it should be a rights-based approach or needs-based approach. One of the main proponents of grounding humanitarian action in rights and laws, Hugo Slim sees a rights-based approach to humanitarianism as giving it an integrated moral, political and legal framework to affirm universal human values.[13] I think that rights and needs go hand-in-hand and there needs to be a more holistic reasoning behind the operations of UNRWA. UNRWA must defend the rights of Palestinians to sustenance and protection, while upholding the principles of humanitarianism needed to ensure that political justification will not be used to withhold aid and violate these rights.

Political Flow of Aid

While the non-political character of UNRWA’s mandate remains unchanged on paper, its assistance has gradually acquired an exceedingly political dimension that has become embedded in the Palestinian nation-building process. This has been primarily due to the evolution of the political context in which UNRWA operates, namely the rise of the Palestinian national movement and the subsequent manifestation of a Palestinian national identity among the refugee communities. As Lex Takkenberg, current Chief of Ethics Office and previous Deputy Director General at UNRWA, explains, “UNRWA was created as a humanitarian agency with a political agenda. Although politics exists in the paperwork, it has been left dormant since the early 60s. UNRWA’s humanitarian mandate has not changed. UNRWA, unlike the UNHCR does not have a statement in its mandate that asks to seek for a durable solution. However, UNRWA has a duty to advocate for a durable solution”.

The manner in which humanitarian aid and politics interfere in UNRWA’s operations is best demonstrated by two examples. One concerns the Oslo accords, which marked a turning point in donors’ attitude toward Palestinians. Prior to these accords, international donors seemed to be indifferent to the need for strengthening the Palestinian society. However, following the Oslo accords, there was a shift in focus to the reinforcement of civil society institutions in the refugee communities and a gradual move towards empowering the population. By late 1998, the total pledged support was over $4 billion although not all of this was actually delivered.[14] There was a preference for funds to be channeled to support peace and civil society-building projects, and not towards the core budget of UNRWA. Another example of the politicization of aid concerns the flow of international aid as well as the tax revenue collected by Israel, supposedly on behalf of the Palestinian government in the West Bank. Israel uses its control over the tax revenue to apply pressure in the political arena, with devastating effects. For example, in July 2011, Israel delayed the transfer of tax revenue, and international donors (including some Arab countries) failed to fulfil their pledge[15].

UNRWA’s assistance is influenced by geopolitics, and without a strong mandate and support from international entities, its service cannot reach satisfactory levels. UNRWA’s inability to prevent budget cuts and securing sufficient quantities of food aid amidst the current situation of political pressure from Israel and its donors, is a clear sign of the humanitarian agenda being hijacked by a political one. While UNRWA runs massive education and health programs, it still struggles to meet the basic food needs of several refugee camps, particularly those in Syria at the onslaught of the recent crisis.

UNRWA is virtually a non-territorial administration, taking on national governmental responsibilities but does not have any legal jurisdiction over either the territory or its inhabitants. This lack of local autonomy argument has been used by Arab countries and Israel to shift responsibility from them to UNRWA. While UNRWA cannot be subordinated to any sovereign government, no sovereign government would submit to the authority of UNRWA. This has led to UNRWA being used as a political pawn by the Arab countries hosting Palestinian refugees.

Members of the Palestinian delegation to the UN cheer the results of a vote granting Palestine non-voting observer status on November 29, 2012. UN Photo/Rick Bajornas

The United States is by far the biggest donor to UNRWA, contributing $294,023,401 in 2013, representing more than 26% of the entire UNRWA budget. The US views UNRWA as a stabilizing force in the Middle East, whose services to the scattered Palestinian refugee population in absence of a solution, prevents social and political upheavals. UNRWA has been expected to avoid political exposure.[16] In order to preserve UNRWA’s ability to provide services to the refugee communities, the organization strives to remain on good terms with all authorities in the region, Arab and Israeli governments, as well as donor countries. UNRWA has abstained from overt cooperation with PLO since this would have led to political controversies. As an organization that is bound by funds originating from countries that have an active political stake in the region, the form and mechanism of delivery of aid by UNRWA is highly politicized.

Arab states have so far officially rejected all schemes of refugee integration, and continue to emphasize UNRWA responsibility for the refugee communities in their territory. The reasons for this seemingly united Arab position are diverse. Jordan remains an exception, granting Jordanian citizenship to the majority of the Palestinian refugees in Jordan. The Lebanese government opposes Palestinian integration, and has repeatedly rejected the implementation of large scale infrastructure projects by UNRWA. Moreover, it was an essential component of PLO’s struggle for national liberation to reject all plans of Palestinian refugee integration. However, following the Oslo Accords, there has been increasing collaboration between the Palestinian Authority (PA) and UNRWA. In the West Bank and Gaza Strip, more and more projects are being implemented jointly by UNRWA and PA. These regions are seemed as test cases for the transfer of UNRWA services to a Palestinian organized body. The PA emphasizes the importance of UNRWA’s existence until a final solution of the refugee problem is achieved. The politics of the Arab states and the PA have major implications on the work that UNRWA does.

Puppets are used as a therapeutic technique in UNRWA schools for children terrified by the sound of bombs and coping with the shock of loosing relatives. Source: desde-palestina.blogspot.com/

The state of Israel is perhaps the biggest political influence on UNRWA’s humanitarian work. Israel has resented UNRWA’s existence for a variety of reasons, but most importantly since the agency symbolized and was a reminder of the human tragedy of Al-Nakba. Israel is opposed to UNRWA reports being discussed at the UN and the extension of UNRWA’s mandate every year[17]. Over the years, Israel has interfered with UNRWA’s operations in a variety of ways, including the bombing of its facilities. On January 6, 2009, there was an Israeli military strike at the UNRWA-run al-Fakhura School in the Jabalia Camp in the Gaza Strip[18]. According to UN and several non-governmental organizations, 42 people were killed, 41 of them civilians. UNRWA attempts to maintain its neutral stance, and in many ways has shielded Palestinian refugees from the Israeli military[19]. Protection extended to the refugees is usually based on humanitarian principles and the agency’s reliance on the basic principles of international law. For example, following the first intifada, UNRWA established the Refugee Affairs Office (RAO) program which resolved issues between the Israeli military and the Palestinians and monitored the camps’ needs for emergency assistance.[20]

Given these facts, one has to conclude that politics plays a huge role in UNRWA’s humanitarian activities, and in turn on Palestinian statehood. Just as the issue is political, so must be the solution. UNRWA’s ability to deliver a satisfactory level of assistance is also limited by a combination of bad policies and bureaucratic dysfunction, in addition to the political constraints. The responsibility for failure does not lie with UNRWA alone, but primarily with the whole system of host countries, donor states, the Palestinian Authority, and Israel.

The failures of specific interventions should not affect the spirit of humanitarian action. Humanitarian agencies should use their power to ensure that their organizations abide by principles and are accountable to their beneficiaries. Thus, UNRWA should continue providing basic services and humanitarian assistance to one of the world’s largest refugee population, but without ignoring the larger political context in which it was created and it currently operates. UNRWA should also try to influence the donors and highlight the refugees’ priorities. Starting a dialogue with the refugees about their vision of implemented activities would help to change the perspective of beneficiaries towards the Agency’s programs.

UNRWA and other humanitarian agencies need to be aware that there is a conflict between traditional humanitarian principles, and the conflict management principles underlying peace and stability. History shows that humanitarian assistance cannot fill the vacuum left by ineffective political arrangements. The challenge for UNRWA and other humanitarian organizations is to understand their role in the growing politicization of aid, to uphold the need for witnessing and the duty of care, and to harness a new consensus for humanitarian principles that is based on a collective respect for humanity. If this trend of political agendas influencing intervention continues, the humanitarian imperative is weakened, and the needs of the victims will go unmet. Understanding and mass awareness of how this New Humanitarianism may radically differ from the principles of humanitarian action should be the first step to counteracting the politicization of aid. International watchdog agencies must be set up in order to disassociate political agenda from the humanitarian imperative. Be it a needs or a rights based approach, delivery of humanitarian aid to those who need it must be at the forefront of the international cooperation agenda. The UN must institute an accountability framework, where any member country found to hinder the humanitarian principles in order to gain political influence will be punished.

UNRWA and the Palestinian Nation-Building Process

UNRWA’s mandate was based on the Economic Survey Mission reports (late 1949), which specifically recommended the socioeconomic integration of the refugees in the host countries through the provision of work opportunities, a large part of the agency’s efforts in the early years involved development/resettlement schemes[21]. It was because of the emphasis on resettlement that UNRWA, despite assurances of the humanitarian nature of its efforts, was from the outset seen in Palestinian political circles as having been created by the Western powers to liquidate the refugees’ political rights through socioeconomic means. Refugee opposition to the resettlement efforts in the early to mid-1950s was such that by the end of the decade, UNRWA was obliged to terminate these programs and reorient its mandate toward general and vocational education[22].

Over the years, UNRWA has set up an administrative infrastructure that is primarily managed in the field by Palestinian staff. This helped preserve a collective, though fragmented, Palestinian identity in exile[23]. Moreover, since UNRWA’s status protected it from interference by host country governments, it rapidly became a forum for Palestinian activism and institutional action. UNRWA establishments, particularly schools and youth centers, have become sites where a collective Palestinian exile identity, grounded on the memory of Palestine and hopes of return, has been created amongst a new generation of refugees who are more nationalistic and politically aware.

UNRWA has been attacked for providing development services to refugees which have been questioned to be detrimental to the concept of Palestinian statehood. Host Arab states and even Palestinian refugees have expressed that sustainable development will integrate the Palestinians in the camps and will erode the zeal for return. UNRWA has consistently denied such claims, as Lex Takkenberg explains, “Your right of return does not depend on the conditions you live in. As long as the plight of the refugees continue, UNRWA has a humanitarian imperative to provide services of quality. This is also a human rights issue.”

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was founded in 1964 with the purpose of creating an independent State of Palestine. It is recognized as the “sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people” by over 100 states with which it holds diplomatic relations, and has enjoyed observer status at the United Nations since 1974.[24] By the time the PLO was established, UNRWA was already deeply integrated in the refugee communities as a provider of welfare and career opportunities. UNRWA’s services were instrumental in ensuring the prosperity of the Palestinian refugee camps, and became bastions of Palestinian nationalism, which was leveraged by PLO as recruiting grounds. Due to its robust position in Lebanon, the PLO used UNRWA facilities for military purposes during the onslaught of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982[25]. PLO has been viewed as a potential threat to UNRWA’s integrity and neutrality due to the political and military stance of PLO[26].

UNRWA’s refusal, usually on technical or financial grounds, to represent Palestinian political interests gave rise to considerable resentment toward the agency. UNRWA has been accused of having a condescending attitude and of “conspiring” against the refugee cause. However, in view of the socioeconomic, political importance and long history of service, criticism of the organization never goes so far as to question the existence of the agency. While PLO is on the forefront of the movement towards Palestinian statehood, UNRWA has strategically positioned itself as a humanitarian organization that looks after the livelihood of the refugees, thus promoting their ambitions of statehood. At the initiative of the UN and the donor countries, UNRWA’s mandate since 1988 has turned into a socioeconomic prop for the future Palestinian state entity, thus resuming, on a smaller scale, the developmental approach the agency had abandoned more than 30 years ago[27]. Since then, UNRWA and PLO have entered into a non-formal agreement of support. While PLO is able to leverage large amounts of funds for UNRWA, particularly from remittances sent from the Gulf States, UNRWA retains control of the choice of projects and their implementation. Given the fact that the United States is by far the biggest financial contributor to UNRWA, this shielding of PLO from UNRWA’s humanitarian and development work is particularly commendable and has ensured long term sustainability of donor funding.

UNRWA seeks to empower the refugee population by initiatives that encourage refugees to prove social relief services of its own[28]. Thus UNRWA has initiated a transition process whereby services would be administered by the Palestinians themselves. The emergence of a sustainable Palestinian state is dependent on the entire Palestinian refugee population overcoming social and economic marginalization, and on their strong will to return. The refugee issue is increasingly seen as a Palestinian problem, rather than an international, or UNRWA problem. This realization has urged the Palestinian leadership to support UNRWA’s development goals, and has gained the support of international entities aligned with the Palestinian statehood aspiration. As Lex Takkenberg describes, “UNRWA has made it clear, and so has its master, the General Assembly, that UNRWA will not go beyond an advocacy role. What we have realized is that – were there to be a political settlement involving some framework agreement including the refugee issue, arrangements made through which Palestinians could choose whether to stay or go to Palestine, compensation, etc. – UNRWA will have to play a very crucial role in the transition.”

It will be premature if UNRWA hands all services to the Palestinian authorities now. Although host Arab countries have welcomed the Palestinian refugees, they are not willing to take responsibility of them. Unlike UNHCR, UNRWA cannot subcontract projects to host countries since they are not willing to take that responsibility. This explains why UNRWA is one of the biggest employers among UN agencies, employing over four times as many employees as UNHCR[29]. However, given the scope and reach of its projects, UNRWA is actually one of the most lean and effective agencies within the UN.

Over the decades, the Palestinian refugees’ vision of return has evolved to an increasingly abstract and incremental process, yet remaining a potent motivating concept. The Palestine of pre-Nakba times has changed, leading to a dissonance between the narrative of grandparents and the discovery of the current generation. The young Palestinian population have no memory other than that of occupation.[30] The efforts of UNRWA towards the improvement in the living standards of refugee population is not seen by the Palestinians as detrimental to their political rights. The refugees have organized themselves in the camps such that they remain collective symbols of organization and the right of return. UNRWA is widely regarded as an indispensable pillar upon which the Palestinian state entity could rely on during the transitional period.

Optimism in the face of an Uncertain Future

In the immediate wake of the Oslo agreements, the gap between the political aims of the Palestinian leadership (focused on state formation) and the refugee communities (which insisted on the right of return) seemed less unbridgeable than originally thought. There was more acceptance of UNRWA’s developmental policy that they were pursuing since the intifada of 1987, from both the refugee population and the Palestinian leadership. As Lex Takkenberg explains, “UNRWA has been part of a natural evolution. Changing circumstances have changed the organization. The 1990s saw the change in focus to social services. Poverty was a huge issue, and only in addressing this UNRWA would live up to its promises. The Lebanese Civil War and the first Intifada led towards a systematic plan of protection for the Palestinians. The optimism of Oslo set a new mindset among the host countries and also the donors. There seemed to be hope in the possible end to this crisis. UNRWA was asked to harmonize the relationship with the host countries, so if the Palestinian state was created, UNRWAs work could be transferred to government ministries of Palestine”.

Absiya Jafari, aged more than 100 years old, holds a Palestinian passport issued during the British Mandate belonging to her husband and herself, in the West Bank village of al-Walaja, 23 November. The original village of al-Walaja was completely destroyed by Zionist forces in 1948. (Anne Paq / ActiveStills)

UNRWA is a major provider of public services such as education, healthcare and microfinance, services that are usually provided by governments. In order to sustain a decent level of service, its budget needs to grow as a function of population growth and inflation. Moreover, UNRWA cannot charge taxes to the beneficiaries of its services. Although the UN has handed UNRWA its mandate, the funds come primarily through donor countries. Due to severe recent budget cuts, the agency has had to stretch itself too thin – putting more students in each classroom, cutting down hospital operation hours, etc. This incompatibility of mandate and funding model has resulted in a deteriorating state of UNRWA’s work which then in turn has implications on the standard of life of the Palestinians.

UNRWA will be there until a political settlement has been reached. Struggling with resource constraints, will make it difficult for UNRWA to do business as usual. Maybe a moment will come when UNRWA will not be able to sustain its services. There are other humanitarian crises that are pulling donor funding. Additionally, 65 years into the Palestine issue, donor fatigue is setting in. When asked what his biggest concern was at UNRWA, Lex Takkenberg answered, “In my 25 years of service at UNRWA, I am scared for the first time that we will not be able to pay our staff. We will be forced to close down some services – perhaps vocational training – things that are not the prime focus like education and healthcare. There is a crisis coming in the next two to four years. Perhaps that is necessary for the international community to re-evaluate UNRWA’s role and the funding crisis.”

UNRWA’s provision of personal rights does not go against the collective rights of the Palestinians. Any discourse regarding this has been detrimental for UNRWA’s efforts in uploading the rights of the Palestinians and in advocating for them. UNRWA as an organization will continue to exist as long as the plight of the Palestinians remains unmet. UNRWA is not an end in itself, but part of the means to an end. While it is difficult to predict the geopolitical conditions of the future, it is only through cooperation between UNRWA, the Palestinian Authority and the Palestinian refugees, that there can be a hope for a meaningful solution to the Palestinian issue.

Conclusion

Few humanitarian organizations around the world can claim the same international entanglements as UNRWA. Whether through the list of nations from which it derives its mandate, or the multinational group of donors who sustain its operations, or the complexity of its relationships with a variety of host governments, UNRWA finds itself permanently mired in international and local politics. While no humanitarian organization engaged in the delivery of aid from the most prosperous to the disadvantaged can maintain total neutrality, UNRWA finds itself forced to engage in the diplomacy of aid. UNRWA has been placed in charge of keeping alive the hope of the Palestinian nation as if it were a quasi-state or a state within a state.

While UNRWA and the politics surrounding it have drawn criticism from the Palestinian refugees, they still support the organization and understand the importance of its existence. The indispensability of UNRWA to life in the Palestinian camps and to the refugees’ survival is recognized by everyone. While UNRWA is arguably the most effective international humanitarian organization, they are bound by a strict mandate and are at the mercy of Middle Eastern instability and political turmoil.

Clearly, what is needed today is a sincere dialogue between UNRWA, the Palestinian Authority and international actors involved in the Palestinian refugee issue aimed at defining the roles and status of each within the framework of the Palestinian nation-state formation process and future of UNRWA.

[1]UNPUBLISHED INTERVIEW: Takkenberg, Lex. Interview by Rahul Mitra. Personal interview. Amman Jordan, May 1st 2014. [2] Benny Morris, “The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited”, pp. 602–604. Cambridge University Press 2004. [3] United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East. “UNRWA in Figures.” Last modified January 1, 2012. [4] Belgrad, Eric A., and Nitza Nachmias. The Politics of International Humanitarian Aid Operations. Westport, Conn: Praeger, 1997. [5] UNRWA. “UNRWA chief calls on East Asian countries to strengthen support.” Accessed May 2, 2014. [6] UNRWA. “UNRWA in Figures.” Accessed April 20, 2014 [7] UNISPAL-United Nations Information System on the Question of Palestine. “Evolution of UNRWA’s mandate to Palestine refugees – Statement of Commissioner-General (21 September 2003).” [8] Schiff, Benjamin N. Refugees Unto the Third Generation: UN Aid to Palestinians. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1995. p. 134 [9] Weiss, Thomas G. “Principles, Politics, and Humanitarian Action.” (1999) [10] United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. “Humanitarian Principles | OCHA.” Accessed April 20, 2014 [11] Duffield, Mark. “Governing the Borderlands: Decoding the Power of Aid Paper presented at a Seminar on: Politics and Humanitarian Aid: Debates, Dilemmas and Dissension. 2001” [12] Fox, Fiona. “New Humanitarianism: Does It Provide a Moral Banner for the 21st Century?” Disasters (2001) [13] Slim, H. “Claiming a humanitarian imperative: NGOs and the cultivation of humanitarian duty.” Refugee Survey Quarterly (2002) [14] Divine, Donna R. “A Very Political Economy: Peacebuilding and Foreign Aid in the West Bank and Gaza; Rex Brynen.” Digest of Middle East Studies (2000) [15] The New York Times “West Bank – Tax Withholding by Israel Will Delay Pay checks for Palestinians – Isabel Kershner.” May 9, 2011 [16] UNRWA – Between Refugee Aid and Power Politics: A Memorandum calling upon International Responsibility of the Palestinian Refugee Question. Gerhard Pulfer and Ingrid Gassner, 1997 [17] Cossali, Paul, and Clive Robson. Stateless in Gaza. London: Zed Books, 1986. [18] Macintyre, Donald; Kim Sengupta (2009-01-07). “Massacre of innocents as UN school is shelled”. London: The Independent. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. [19] Ibid., 120-1 [20] Rempel, T. “UNRWA and the Palestine Refugees: A Genealogy of “Participatory” Development.” Refugee Survey Quarterly (2009) [21] UNISPAL-United Nations Information System on the Question of Palestine. “Mideast situation/Palestine refugees – Economic Survey Mission for the Middle East final report signed – Press release (19 December 1949).” [22] Rosenfeld, M. “From Emergency Relief Assistance to Human Development and Back: UNRWA and the Palestinian Refugees, 1950-2009.” Refugee Survey Quarterly (2009) [23] Khalidi, Rashid I., Baruch Kimmerling, and Joel S. Migdal. “Palestinians: The Making of a People.” American Historical Review (1994) [24] United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3210 [25] Brynen, Rex, and Benjamin N. Schiff. “Refugees unto the Third Generation: UN Aid to Palestinians.” American Historical Review (1998) [26] “The Report of the Commissioner- General of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East” June 1969-June 1970 [27] UN General Assembly Resolution 19 48/40, Aid to the Palestine Refugees, 10 December 1993 [28] Joint Programme Proposal, “Gender Equality And Women’s Empowerment In The Occupied Palestinian Territory” 2008-2011 [29] Niklaus Steiner, Mark Gibney, Gil Loescher, Problems of Protection: The UNHCR Refugees and Human Rights. Routledge, Apr 30, 2003 [30] Georges E. Bisharat, “Displacement and Social Identity: Palestinian Refugees in the West Bank,” in Population Displacement and Resettlement: Development and Conflict in the Middle East, ed. by Setenay Shami (New York: Center for Migration Studies, 1994), p. 178.

A traveler’s guide to Dhaka, Bangladesh

Dhaka is so much more than just a city. It is a whirlpool that pulls anything and anyone that comes close to it – sending them around and around like some wildly spinning fairground ride bursting with energy. It is organized chaos – millions of individual pursuits churning together into frenetic collective activity. I cannot guarantee you’ll fall for Dhaka’s many charms, but sooner or later you will start to move to its beat. And when that happens, Dhaka stops being a terrifying ride and starts to become a unique blend of art and intellect, passion and poverty, love and hate.

The charms of Dhaka are not immediately visible to the naked eye – they are dhaka (hidden in Bengali). Not that there are hordes of visitors trying to uncover those charms; this is a city that remains largely untouched by tourists. The city is what it is, a place in perpetual motion, the glorious chaos of which is perhaps best viewed from the back of one of the city’s half-a-million colorful rickshaws. As someone who has called this place his home for some 20 years, here is my list of the essential things-to-do/sights-to-see while in Dhaka.

1. Take a rickshaw through the busy streets

There are cycle-rickshaws all over Asia, but in Bangladesh they are more colorful, more prevalent and more integral to everyday life than anywhere else. Rickshaws are an art form in their own right. They are plentiful around Dhaka, and the best way to explore the city like a local. They are cheap, fun, environmentally friendly and are often the quickest way to get through the busy streets. And speaking of busy streets, might I add that Dhaka has some of the worst traffic in the world. You may find yourself amongst a standstill – rickshaw drives screaming, buses honking, traffic lights functioning as mere decorations. But this is just part of the city. So sit back and enjoy this organized chaos!

2. Explore Old Dhaka

For some, the assault on the senses is too much to handle, but for others, the unrivaled mayhem that is squeezed into the narrow streets of Old Dhaka is simply delightful. No matter where you’ve come from, or what big cities you’ve visited before, Old Dhaka will knock you for six (a cricket reference) with its manic streets and nonstop noise and commotion. Nestled in the cacophony are structures from a bygone era – Ahsan Manjil, home of the Nawabs, and the Lalbag Kella, a Mughal fort. Some of the most amazing food in the city is to be had in hole-in-the-wall stores such as Haji Biryani and Nana Biryani.

3. A boat ride on Buriganga

Running calmly through the center of Old Dhaka, the Buriganga River (Old Lady Ganga) is the muddy artery of Dhaka and the very lifeblood of the city, and perhaps the nation. To explore it from the deck of a small boat is to see Bangladesh at its most raw and gritty. The panorama of river life is fascinating. Boats of all shape and size compete for space and motion, with children dotting the foreshores, fishing with homemade nets. On the banks of the river is Shadarghat, perhaps one of the busiest loading docks in existence. You can take a rocket (steamboat) to other cities in Bangladesh – Barisal, Comilla and Chandpur to name a few. As you cross from Dhaka to Old Dhaka to the Buriganga, life speeds up, and then hits the brakes to arrive at a watery sunset.

4. Drink a cha, eat some fuchka

Dhaka runs on cha (or chai). These sweet, milky, hot cups of tea are a Bangladeshi style caffeine fix. Add some street food, and you have got yourself the perfect desi snack. The local street food fare includes fuchka, chatpati, and jhalmuri to name just a few. Head to Dhanmondi Lake or just about any intersection in the city to get your daily dose of some of the best street food you’ll ever taste.

5. Sangsad Bhaban

The parliament building of Bangladesh is a true architectural masterpiece – the magnum opus of the American architect, Louis Kahn. It blends motifs from ruined monuments and Bangladesh’s topography, with a remarkable use of natural light. The Sangsad Bhaban lies on a vast area in the middle of the city, seemingly floating on a lake, a refuge within the bustling city.

6. Festivals

Festivals have always played a significant role in the life of the people of Bangladesh. They are parts and parcels of Bengali culture and tradition, and no matter when you visit Dhaka, there’s indefinitely one to find. Here’s a list of some of the bigger ones:

- Pahela Baishakh – The advent of Bengali New Year is celebrated throughout the country. The best place to celebrate is Ramna Park, where perhaps a million people will take part in an exhibition of Bengali culture. Make sure to grab a plate of panta rice with Elish fish while you are there. Pahela Baishakh follows the Bengali calendar and takes place mid-April.

- Shadhinota Dibosh – The independence day of Bangladesh is March 26. Independent for four decades, the war is still a huge part of society here and the independence day is a show of nationalistic pride. Citizens including government leaders and sociopolitical organizations and freedom fighters place floral wreaths at the National Martyrs Monument at Savar. At night the city is illuminated with lights.

- Ekushey February – The 21st of February is observed throughout the country to pay homage to the martyrs’ of Language Movement of 1952. It is now regarded as the World Mother Language Day. This is quite a unique occasion – somewhere in between a festival and a mourning day. The Shahid Minar (martyrs monument) is the symbol of sacrifice for Bangla, the mother tongue.

- Nabanno, Eid, Durga Puja, and others – There’s almost too many to list here, but Nabanno (festival of the new harvest), Eid and Durga Puja just have to mentioned. No matter what your religion, Eid and Puja are cause of celebration in Dhaka.

7. Explore the history

Bangladesh is probably one of the few nations whose citizens have experienced two independence struggles – from from British colonial rule and then liberation from Pakistan in 1971. Although the war was over four decades ago, its presence is everywhere. It’s hard to open a paper, speak to a writer, or discuss politics without hearing the words “71,” “martyr” or “freedom fighter.” The Liberation War Museum is a fascinating if at times gruesome look at that struggle, with lots of press clippings and other memorabilia from that time. If you’re new to Bangladesh, this is an important starting point for understanding the national obsession.

8. The mosque and the temple

Dhaka is dotted with numerous mosques and temples. These are more than just religious institutions, since religion and culture are so intertwined in peoples lives in Bangladesh. Head to the 1,200 year old Dhakeshwari Temple, the center of the Hindu religion in Dhaka and then to the Tara Masjid, the beautiful 18th century mosque adorned with mosaic stars. You don’t have to belong to any particular faith to appreciate the beauty of these structures, and in doing so, you’ll get a glimpse of an integral part of culture and society here.

9. Art, music and literature

Bangladesh is rich in art, music and literature, and there are few better places to get a taste of the arts than Dhaka. Head to the Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts or the Drik Gallery to sample some of the contemporary art, which frequently makes a social commentary. The music scene in Dhaka is HUGE! From the classical works of Rabindranath Tagore and Nazrul Islam, to pop and heavy metal – there’s a concert to go to for everyone. Follow ConcertNews to find the next one.

Bengalis love to read, and there’s no better place to experience this passion for books than Nilkhet. Sandwiched between Dhaka University and New Market, this labyrinth of bookstores will satisfy and enlighten even the best-read visitor. Dhaka also hosts one of the biggest book fairs in the world, the Ekushey Book Fair.

And if you’re in the mood for shopping, you are in luck. Dhaka is one of the shopping hubs of South Asia. Head to New Market, Doyel Chattor, Bashundhara or Chandni Chawk and you will find pretty much anything.

10. Add yours here!

I started to write this thinking I’ll list 10 things. But to pick 10 things to do in this megalopolis that is home to me, is almost impossible. I’ll keep adding recommendations as comments, and I ask my readers to do so too. I don’t expect, or want Dhaka to turn into a tourist destination. But I want it to be appreciated for what it is – a city in perpetual motion, an experience that will side-swipe you with its overwhelming intensity, leaving impressions that will never fade.

CREER – A Partnership between Rincon, Panama and EWB-DC

Three years ago, I traveled to the community of Rincon in the Ngöbe-Buglé Comarca of Panama to visit my friend Gillian, who was working there as a community mobilizer with the organization Health Empowering Humanity. The Comarca is inhabited by the Ngöbe-Buglé indigenous tribe – one of the most historically marginalized tribes in Central America. The community members upon finding out about my work with Engineers Without Borders, asked me if we could help them build an educational resource center to improve the quality of education and provide access to information. While I didn’t make any promises, I pointed them to the EWB-USA website and the application to initiate a new project. Two months later, I found in my inbox a completed application and a letter, signed by the students in Rincon, requesting the support of Ingenieros Sin Fronteras. Thus started CREER – Centro de Recursos Educativos en Rincon, a partnership between the people of Rincon and Engineers Without Borders – Washington, DC.

The Ngöbe-Buglé

Panama has one of the stronger economies in Central America; however, it also has the highest level of economic inequality in the region and the third highest in the Americas. In the Comarca Ngöbe-Buglé, the indigenous state of the largest indigenous group in Panama, the satisfaction of basic needs is the lowest in the country. Within the Comarca, the maternal mortality rates skyrockets from Panama’s average of 70 deaths per 100,000 live births to a shocking 658 deaths per 100,000 live births—higher than that of Haiti. The resources to address these disparities exist within the country, but they are badly distributed and the residents of the Comarca often ill-equipped to demand and manage these improvements.

Historically marginalized, most Ngöbe-Buglé communities lack the most basic needs – clean water, sanitation, clinics and schools. Living in the Panamanian highlands, not only are they geographically isolated, they are also social excluded. Faced with this dire situation, their indigenous customs and way of life is threatened. The Ngöbe-Buglé students find it difficult to compete with other students in Panama, while the youth lack employment opportunities. This stark poverty has perpetuated over generations, relegating the community in a poverty trap. While struggling to make ends meet, the Ngöbe-Buglé are a resilient people, and want to progress their communities to the future, while maintaining their indigenous roots.

Hato Rincon

Rincon, or Jädeberi (ha-deh-berry) in the language of Ngäbere, is a set of remote mountain communities, with 1600 residents, located in the Ngöbe-Buglé Comarca. The residents of Rincon are primarily subsistence farmers, although many leave the Comarca to work as laborers in other cities in Panama. While the people of Rincon lack most government services, they are extremely well organized and have built their own water system, latrines, communal buildings and fishponds. Much of this work was encouraged by the work of Health Empowering Humanity (HEH) who have been working in the community since 2009. HEH and the community mobilizers they posted to Rincon, strengthened local ability to evaluate, plan, and carry out health and development projects. HEH, and two of it’s community mobilizers, Monica Dyer and Gillian Locascio, introduced EWB to Rincon and have been instrumental in the establishment of the project.

This region of Panama has limited educational opportunities. Students graduating from local schools and starting high school outside of the area have often never used a computer. Nevertheless, they find themselves competing with students who have been using computers and the internet for years, and often their success rates at high school level and their chances of continuing education in universities are negatively impacted. Moreover, for the communities in the area, access to crucial information including best practices in sustainable development from other regions, national and international current events, modern science, and international funding sources and opportunities are restricted to what is aired on the radio. Even in the process of requesting government support for local projects, documents often must be typed and printed. This requires a prohibitively expensive and time intensive trip to the nearest computer center (5 hour journey) and knowledge of computers. For this reason, the people of Rincon has requested Engineers Without Borders to help them realize their dream of a local computer center and library.

CREER (Centro de Recursos Educativos en Rincon)

CREER (Believe in Spanish), is a partnership between the people of Rincon and EWB-DC, that seeks to improve the quality of education and provide access to information and communication technologies to the Ngöbe-Buglé. Together, we will construct a center that will house a computer lab and a library, while also serving as a community center. These computers will be powered by an alternative energy source (solar, wind, or hydroelectric) and connected to the internet via satellite.

CREER will allow the Ngöbe-Buglé students to augment their studies with computer training, and compete on a level playing field with others across Panama. The initial plan is for the center to be open to the public, charging a nominal fee for computer usage so the center can sustain itself. The community members have also expressed interest in telemedicine and documenting their indigenous folklore using the computer and the internet. One day we may even see the community using the resources to start an internet radio station, broadcasting for the first time in Ngäbere.

Rincon – EWB-DC Partnership

While Engineers Without Borders will provide the engineering oversight for the project, the community of Rincon will provide the manual labor, locally available skills and materials and will be in charge of the operation and maintenance of the infrastructure. Rincon will also contribute at least 5% of the construction cost, while the rest will be financed by EWB through grants and in-kind donations. The EWB CREER team is comprised of a dedicated group of engineers, public health and education specialists, architects, students and professionals from a wide range of backgrounds. The group meets every other week, and we are always looking for new members. So do join if you’re interested and happen to be in the DC area!

This project is very personal to me – not because I was there during its initiation, but because I believe in the power of such collaboration to make a lasting impact in the world. The citizens of Rincon are some of the warmest people I have met, and I stand to learn a lot from their perseverance in the face of adversity. I am so happy that there is now an entire team of passionate individuals working on this. At the nexus of the efforts of the team in DC and the community of Rincon, there will be CREER – an institution where dreams are turned into reality.

The Impact of the Syrian Crises on Palestinian Refugees

As Syria witnesses what has evolved into a full-blown civil war, the Palestinian refugees in Syria are in a particularly precarious position given their refugee status in the country. The fast evolving positions of key international players could see the ongoing mayhem in Syria evolve into an altogether unforeseen direction[1]. During these times of uncertainty, one thing is certain – the Palestinian refugees and their demands for a better future continue to suffer due to the entanglement of their aspirations with contradictory regional and international geo-political interests.

This article examines how the events in Syria over the past three year have impacted the Palestinians in the country and assesses the possible implications of the ongoing upheaval and uncertainty for this particular community. The paper concludes by arguing that the fate of the Palestinians, like that of the Syrian people, not only remains uncertain, but is also particularly perilous given their refugee politico-legal status in Syria. The geopolitical situation in the region has in the past, and continues to take a heavy toll on the Palestinian refugees.

The Palestinians in Syria

Of the 726,000 Palestinians that escaped during the Nakba or first exodus in 1948, an estimated 85,000- 90,000 Palestinians fled to Syria[2]. The over half a million Palestinians living in Syria before the start of the civil war are mostly descendants of refugees who arrived then. These refugees fall under the mandate of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA).[3] This population have enjoyed unparalleled rights when compared to other Palestinian refugees – they can hold passports, own homes and take jobs. Palestinians benefited from the Baath party’s absolute support and the reality of these rights, coupled with the place of Palestine in Arab nationalist ideology and rhetoric, has allowed for the Palestinians’ unique civil rights and relative stability in Syria while shoring the regime’s Arab nationalist credentials.[4] These refugees first settled in overcrowded residential quarters, residing in abandoned schools, and other public institutions. Later official refugee campus, such as the Yarmouk camp in the outskirts of Damascus, were established and operated by UNRWA. In many ways, the camps in Syria were much better compared to other Palestinian camps in the neighboring Arab states. However, once Bashar al-Assad’s rule was challenged, the old dogmas and rivalries drove the Palestinians into despair. The Palestinian credentials and political alignments, played a dangerous role in a backlash against the community at the onslaught of the civil war.

The Onslaught of the Civil War

Since the beginning of the conflict in Syria in March 2011, more than one million Syrians have been internally displaced. More than 700,000 have fled to neighboring countries[5]. However, these figures do not include those not registered with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), suggesting that these numbers might in actuality be significantly higher.

Approximately 235,000 Palestine refugees from Syria are displaced in Syria, while over 60,000 have fled the country[6]. Palestine refugees from Syria have been severely affected by the ongoing armed conflict. Almost all of their residential areas have experienced armed engagements or the use of heavy weapons. The massively underfunded UNRWA is struggling to provide assistance to these groups, both internally displaced in Syria, and forced to migrate to neighboring countries. As of February 2014, UNRWA lacks 91.60% of the funds it needs to address the needs of these displaced population[7].

There were reports that Jordan and Lebanon have turned away Palestinian refugees attempting to flee the humanitarian crises in Syria. Jordan has absorbed 126,000 Syrian refugees, but Palestinians fleeing Syria are placed in a separate refugee camp, under stricter conditions and are banned from entering Jordanian cities[8]. Faced with no options, many Palestinian refugees are seeking asylum in Europe. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine claimed in October, 2013 that over 23,000 Palestinian refugees from the Yarmouk Camp in Syria had immigrated to Sweden alone. Due to the rapidly shifting landscape and lack of robust information from the crises, the effect of the Syrian civil war on the Palestinian refugees is best studied through the case studies. The following section presents two case studies – one of Palestinian refugees from Syria in Lebanon, and the other from the Yarmouk Refugee Camp in Damascus.

Case Study: Palestinian Refugees from Syria in Lebanon

As of November 2013, more than 51,000 Palestinians displaced from Syria have registered with UNRWA in Lebanon[9]. Refugees twice over, they are special cases because they are to be served by UNRWA rather than UNHCR, according to UN mandates. UNRWA is chronically underfunded and ill-equipped to manage such a large and rapid influx of Palestinian refugees. Already overcrowded and very poorly equipped to meet the needs of refugee influx, the existing UNRWA structures in Lebanon – schools, health clinics, and social services – are struggling to keep up the pace with this fast evolving crisis.

In March 2013, American Near East Refugee Aid (ANERA) conducted a needs assessment of the Palestinian refugees from Syria displaced by the civil war[10]. The results of the survey provides an insight into the disruptive effects of the war on this already vulnerable population. The survey showed that 96.5% of families witnessed armed conflict while in Syria. About 94% of the surveyed group lived through some type of personal traumatic experiences, including death in the family, physical trauma, or home destruction. The makeshift camps set up by UNRWA in Lebanon lacks the most basic of services, and urgent needs such as appropriate psychological evaluation and intervention, is mostly neglected.

The livelihoods of the Palestinian refugees from Syria differ greatly from the general Syrian refugee population living in Lebanon. Palestinian refugees from Syria do not have the automatic right to employment in Lebanon while Syrian citizens do. They lack both the legal framework and informal social networks related to employment, which can provide a vital economic lifeline in this crisis.

This survey also discovered that only 10% of working age Palestinian refugees from Syria are employed in Lebanon. It should also be mentioned that more than one-third of the working-age members of this population were unemployed in Syria, and due to the lack of educational opportunities and training in Syria, they come to Lebanon already at a disadvantage. With no end in sight, the Palestinian refugees from Syria face prolonged displacement in Lebanon and their inability to financially sustain themselves in Lebanon makes them particularly vulnerable.

Case study: Yarmouk Camp in Damascus

Yarmouk was established in 1957 on an area of 2.11 square kilometers to accommodate Palestinian refugees forced out of their homeland following the Nakba[11]. Over time, refugees living in Yarmouk have strived to improve their residences and public institutions in the camp. Before the war, living conditions in Yarmouk were significantly better than in Palestinian refugee camps in other parts of the Arab world. The majority of the residents in Yarmouk were second and third generation Palestinians and in many ways had incorporated into the Syrian population, taking up professions such as medicine, engineering and civil service. However, as the Syrian war intensified, Yarmouk struggled to remain neutral. There were clashes between those who supported the largely Sunni anti-government opposition and those who favored staying out or who backed the regime dominated by Alawites. Rebel forces marched into Yarmouk and took control, leading to the majority of the civilian population to flee. The Syrian army then blockaded and bombarded Yarmouk. Of its 250,000 Palestinians, scarcely 18,000 now remain. UNRWA reports that up to 1,500 people have died, many of them due to hunger[12].

The ongoing battle between the Free Syrian Army, rebel forces and the Syrian army has disrupted the flow of crucial aid to the civilian population. Infant malnutrition, maternal mortality and starvation is now a fact of life in Yarmouk. Recent peace talks in Geneva have allowed some aid to trickle into the camp, and the safe passage of some civilians out of Yarmouk[13].

Conclusion

Through the analysis of case studies presented in this paper, it can be said that the Palestinian refugees in Syria represent one of the worst affected groups following the Syrian civil war. The scale of the Syria conflict and its devastating humanitarian consequences continue to outstrip forecasts and planning scenarios set forth by UNRWA and aid organizations. In light of the particular vulnerability of this refugee population, the international community must collectively work to ensure the following:

- Preserve the resilience of Palestinian communities, including those displaced inside Syria and those forced to flee to neighboring countries.

- Provide a protective framework for Palestinian communities and provide access to basic services

- Strengthen humanitarian capacity and coordination to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of emergency program delivery

[1] Anaheed Al-Hardan, “A Year On: The Palestinians in Syria,” Syrian Studies Association Bulletin, 17, no. 1 (2012)

[2] Hadia Hakim, “Palestinian Identity-Formation in Yarmouk: Constructing National Identity through the

Development of Space”, 2009

[3] “Syria,” United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East,

[4] Al-Hardan, Anaheed, “The Right of Return Movement in Syria: Building a Culture of Return, Mobilizing

Memories for the Return,” Journal of Palestine Studies 41, no. 2, (2012), pp. 62-79.

[5] Accessed February 24, 2014. http://www.unrwa.org/syria-crisis

[6] “RSS in Syria”. UNRWA. 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

[7] Accessed February 24, 2014. http://www.unrwa.org/sites/default/files/regional_prs_appeal.pdf

[8] Times of Israel. “Jordan Turns away Palestinian Refugees” http://www.timesofisrael.com/jordan-turns-away-palestinian-refugees-fleeing-violence-in-syria/

[10] ANERA, “Palestinian Refugees from Syria in Lebanon: A Needs Assessment”, March 2013

[11] “Yarmouk: Unofficial Refugee Camp”. UNRWA. 30 June 2002.

[12] Robert Fish, “Yarmouk: A camp without hope for a people without a land”, The Independent, January 2014

[13] LA Times, “Impasse imperils Syria aid deal reached at Geneva peace talks”, January 2014

Stay updated with our travel team!

I am co-leading an Engineers Without Borders trip to Cameroon for two weeks! Follow our team updates here!

Hello family, friends, and other curious onlookers! It’s now less than a week before our intrepid group of engineers and public health professionals departs for the Mbokop community in Cameroon. For those just tuning in, this trip will be a follow-up of our very successful first trip to the community in March 2013.

This time around, EWB team members Lisa, Lauren, Rachel, Gavin, Brennen, Victor, and Rahul, along with HEDECS, our in-country partner NGO, will be continuing where we left off last time with public health surveys and assessment of the current water infrastructure in the community. Additionally they’ll be conducting topographic surveys for a new water distribution system and visiting schools to introduce health and hygiene education materials.

We (Stephanie and Ben) will be keeping family and friends updated daily on the status of our travelers through email, Facebook, Twitter, and of course this blog. Some posts…

View original post 65 more words

Gender in Development : A Case Study of Bangladesh

Headlines and reports would have us believe that women have reached gender parity in Bangladesh. The female under-five mortality rate is 20 per cent lower than that of boys; girls are participating more, and better in primary education; and female work force participation rate has rapidly increased in the past decade. The prime minister and leader of the opposition are both women, and have ruled back and forth for more than 20 years. However, a thorough gender analysis reveals intrinsic gender inequalities imbued into Bangladeshi institutions and the social fabric, making a profound impact on development, cultural and economic outcomes. Efforts to promote gender equality has been undermined by a patriarchal social structure reinforced by religious, economic and political norms. This report analyzes the status of women in Bangladesh, and the role that gender plays in development outcomes.

Introduction

The socio-cultural environment in Bangladesh contains persistent gender discrimination that hinders the development outcome of women, and the country. The political institution has made great strides towards gender inclusion, however the cultural institution has made significant progress in women’s empowerment impossible. Girls are often considered to be financial burdens on their family, receiving less investment in their health and education from the time of birth. However, recently there has been noteworthy advancements in the health and educational outcome of girls due to laws promoting education – both for girls and mothers.

As girls approach puberty, the differences in the way that they are treated in comparison to adolescent boys, becomes more prominent. Adolescence is viewed as an abrupt shift from childhood to adulthood, and not as a distinct phase of life. In rural communities, where the majority of Bangladeshis live, adolescence is when boys start working. For girls however, mobility is often restricted, limiting their access to livelihood, learning and recreational and social activities.

Bangladesh has one of the highest rates of child marriage and adolescent motherhood in the world. In 2011, the maternal mortality rate was reported as a high 220 per 100,000 live births[i]. Violence against women is another major impediment to women’s development.

The following is an analysis of the status of women in Bangladesh across several pertinent issues. It will be evident that although the political institution and emerging democratic values have seen the country make great progress in gender equality, the sociocultural institution reinforced by religious norms has hindered progress and perpetuated patriarchal values.

Health and Education

Traditionally in Bangladesh, preference has been given to the boy child, and this discrimination led to higher girl child mortality due to unequal provision of health care and less attention for girls. However, over the past decade girl’s health and education have improved drastically. Today, the female under-five mortality rate is significantly below that of boys, indicating that at this early stage in life, there is no sign of a non-natural gender bias[ii].

However, a closer analysis of the sex ratio reveals a disturbing picture. There are 107.5 males for every 100 females in Bangladesh, a ratio that is worryingly higher than the normal human sex ratio[iii]. There is a strong cultural preference for boys over girls in the male-dominated society of Bangladesh which exacerbates this imbalance. As girls grow up, reach puberty and become adolescents, the biological advantage with which they were born yields to the weight of cultural and societal norms which shape gender differences that limit the full enjoyment of their rights.

In education, the gender parity is strongly tilted in favor of girls (gender parity index in primary education is 103 and in secondary education a very high 117). Girls are participating more, and better, in primary education. A disproportionate higher number of girls are reaching grade 5(national definition of literacy), which will eventually result in a society where more women are educated than men. However, in adolescence, female school dropout rates soar. These rates are strongly related to social conduct norms such as not allowing girls to leave their home unaccompanied, being subject to sexual harassment (eveteasing), and physical violence. School drop-out rates are also strongly related to child marriage, a pervasive practice in Bangladesh despite existing legislation banning it.

Ownership Rights and Civil Liberties

Despite women’s growing role in agriculture, social and customary practices virtually exclude women from having direct ownership of land. A woman’s lack of mobility, particularly in rural areas, forces her to depend on male relatives for any entrepreneurial activities. While microfinance has expanded throughout Bangladesh, there is a growing concern to whether or not these women actually retain control over the loans they receive. According to the national law, men and women have equal rights to property, but in practice women have only very limited access to property. Their situation is further impaired by discriminatory inheritance laws that are dictated more by religious laws/norms than state legislation. Moreover, due to perceptions of women’s role in society and the household, Bangladeshi women are most often not likely to claim their share of family property unless it is given to them.

Despite being a predominantly Muslim country, most civil liberties extend to women in Bangladesh, particularly in urban areas. In rural Bangladesh, depending on the traditions of individual families, the Islamic system of Purdah impose some restrictions on women’s participation in activities outside the home, such as education, employment and social activities. To engage in any such activities, a woman generally needs her husband’s permission. Discrimination in civil rights and liberties in Bangladesh result in decreased economic and social outcomes that are felt both at the household and national levels.

Employment in the Formal Sector

Women’s participation in economic activity has increased in both rural and urban Bangladesh. The established garments production sector employs over 1.2 million workers, 74% of whom are women. Women’s employment rates remain low despite progress, and their wages are roughly 60-65 per cent of male wages[iv]. This wage differential by gender is widest in nonagricultural employment, in both rural and urban areas. In rural areas, women are primarily employed in the lowest productivity sectors. The Bangladeshi government has introduced legislation that guarantees women a specified percentage of public sector employment but the quotas have never been filled, and there is no system for monitoring or implementing them[v].

Political Representation

Although the prime minister and leader of the opposition party are both women, there remains an unequal power relation in the political arena. Many women politicians, including the prime minister and leader of the opposition, hail from influential political families. Despite the low participation rate of women in the political arena, state policies promote equality. For example, at the regional (Union Parishad) parliament, 25% of seats are reserved for women[vi]. However, the Bangladeshi cultural institution discourages women from entering the political world through the pre-existing social norms that associate leadership with men. Overall, women’s participation in the political arena on the local, regional or state levels remains a rarity. The under-representation of women in parliament results in legislation that is gender insensitive.

Access to Capital

Bangladesh has seen a boom in organizations active in the area of credit provision. The government also operates subsidized credit programs targeted towards rural women that reaches over 20 percent of the rural population[vii]. Although women participate in such programs, the extent to which they alleviate women’s poverty and improve their position as economic actors is not so clear. There exist sociocultural barriers that prohibit women from entrepreneurship. Moreover, due to historically low rates of education and training among adult women, the productivity of loans tend to be lower than that for men. There needs to be a focus shift on improving women’s access to market as a means of enhancing the use of capital and also meeting women’s empowerment objectives.

Gender-based violence

The different manifestations of violence against women have the same premise of deep-rooted attitudes and beliefs that are perpetuated by the cultural institution in Bangladesh. The government has enacted numerous laws protecting women, and has passed landmark court decisions over the last decade. However, the patriarchal legal system that governs rural communities allow crimes perpetrated against women to continue unabated. In 2000, the Supreme Court ordered every incident of eve-teasing to be considered ‘sexual harassment’[viii]. Other laws protecting Bangladeshi women from various forms of violence include the Acid Crime Control Act 2002 and the Dowry Prohibition Act 1980. The existence of laws is an important first step towards social justice for girls and women’s rights, however without full enforcement, the laws are meaningless. Moreover, without a shift in the underlying attitudes towards women’s role in society, any initiative to abate gender-based violence will be unsustainable.

Poverty

One third of the Bangladeshi population lives below the poverty line. While poverty stimulates gender inequality, the reverse also holds true. The aforementioned factors of gender inequality has sustained poverty among women. In spite of increasing awareness of the economic and social values of women’s role in Bangladesh’s development, the economic progress of women has been mired by cultural dogmas. In Bangladesh, 62 percent of the women are economically active, which not only ranks above the average of 50 percent for developing countries, but also is the highest rate in South Asia. However, despite a high proportion of women in the labor force, the share of total earned income for women is less than one quarter. Overall women have made little gains in economic well-being and Bangladesh has seen the “feminization of poverty”.[ix]

Conclusion

The political and sociocultural institutions have divergent impacts on women’s development in Bangladesh. Perceptions of women’s role in society has negatively impacted the country’s economic and social output. Cultural and social influences and practices, including the distorted interpretation of religious texts have resulted in an imbalanced society. Concerted efforts are required to raise awareness and educate on gender equality at all levels of society – from grassroots initiatives to governmental policies. Moreover, women must be empowered to challenge social norms that are detrimental to the human rights of women. Education, change in social norms and conditions, a conducive political and legal environment, and girls and women’s empowerment will help break the vicious cycle of gender disparity. Only when the political and cultural institutions in Bangladesh act in unison will this be realized.

[i] Every Mother Counts, Bangladesh Factsheet 2012

[ii] UNICEF, Women and girls in Bangladesh

[iii] UNICEF, A perspective on gender equality in Bangladesh

[iv] The World Bank, Whispers to Voices: Gender and Social Transformation in Bangladesh 2008

[v] War on Want – Stitched Up – Women workers in the Bangladeshi garment sector

[vi] Asia Foundation, Are Bangladeshi Women Politicians Tokens in the Political Arena?

[vii] Jonathan Morduch, The role of subsidies in microfinance: evidence from the Grameen Bank

[viii] Prevention of Women and Child Repression Act, Bangladesh, 2000

[ix] Sylvia Chant, The ‘Feminisation of Poverty’ and the ‘Feminisation’ of Anti-Poverty Programmes: Room for Revision?

Call for presenters Global Forum on Statelessness